For students and teachers alike. Help to develop your thinking skills with exercises and discussion.

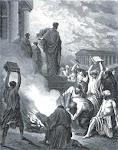

Burn your Books !

Think for yourself instead.

Socratic Questioning

Socrates was an annoying old man who would ask awkward questions like;

"What exactly do you mean by that? " or

" What do you mean by Truth?" or

"Does what you say now agree with what you said before?"

Questioning is at the heart of critical thinking so many exercises can be based on these six types of Socratic questions: [See link]

Vital Links

Inference

Exercises

Types of Argument

Many people distinguish between two basic kinds of argument: inductive and deductive. Induction is usually described as moving from the specific to the general, while deduction begins with the general and ends with the specific; arguments based on experience or observation are best expressed inductively, while arguments based on laws, rules, or other widely accepted principles are best expressed deductively. Consider the following example:

| Adham: I've noticed previously that every time I kick a ball up, it comes back down, so I guess this next time when I kick it up, it will come back down, too. Rizik: That's Newton's Law. Everything that goes up must come down. And so, if you kick the ball up, it must come down. |

Adham is using inductive reasoning, arguing from observation, while Rizik is using deductive reasoning, arguing from the law of gravity. Rizik's argument is clearly from the general (the law of gravity) to the specific (this kick); Adham's argument may be less obviously from the specific (each individual instance in which he has observed balls being kicked up and coming back down) to the general (the prediction that a similar event will result in a similar outcome in the future) because he has stated it in terms only of the next similar event--the next time he kicks the ball.

Thinking about Life

Who am I?

Where do I belong?

How should I live my life?

Our religion answers these questions, but we still have to think about them clearly and critically.

As Socrates said,

"The Unexamined Life is not worth living."

'

Six Types of Question

2 Questions that probe assumptions

3 Questions that probe reasons and evidence

4 Questions about Viewpoints and Perspectives

5 Questions that probe implications and consequences

6 Questions about the question